This post is the first of a series, where I will educate you about things about the Looney Tunes cartoons that most people don’t know.

The Looney Tunes are among the most famous cartoon characters in the world. The gang of Bug Bunny, Daffy Duck, Porky Pig, Elmer Fudd, Sylvester, Tweety, Marvin the Martian, Yosemite Sam, Foghorn Leghorn, and the Tasmania Devil are loved around the world for their humor and overall zaniness.

However, it did not start with them. It was several years before such characters first saw the light of day and became famous.

First, let’s step back in time to the late 1920’s. There were two animators named Rudof Ising and Hugh Harman. They worked for Walt Disney on the Oswald the Lucky Rabbit cartoons for Universal. Things were good, and the cartoons were a success.

Then Disney had Oswald taken from, as he owned no legal rights to Oswald.

Charles Mintz, Disney’s distributor, set up a new studio, and hired away most of the staff including Harman and Ising. They made more Oswald cartoons, but things went south. Disney struck gold with Mickey Mouse, and Universal was angry that Mintz had let him go. After failed attempts to get Disney to come back, Mintz and his studio was dismissed by Universal, and they hired Walter Lantz to make cartoons for them.

Harman and Ising were in need of another job. Harman had previously created Bosko and copyrighted him, so that no one could take him from them.

They created a short pilot cartoon called Bosko the Talk-Ink Kid, which is credited as being the first animated cartoon with extended dialogue. This short pilot got the attention of film producer Leon Schlesinger who decided to feature Bosko in a series of cartoons that he would sell to Warner Bros. called the Looney Tunes. The short was not seen publically until the around the beginning of the 21st century.

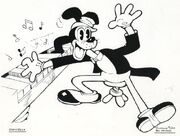

Bosko was first seen by a public audience in 1930 in a cartoon called Sinkin’ in the Bathtub which was first appearance of his girlfriend, Honey. From then, Bosko starred in 38 more cartoons, and he proved to be quite popular.

Bosko’s cartoons are noted for having little to no plot, and for their reliance on music.

There is also the nature of the character himself. Nowadays, Bosko is often deemed an offensive character because his design is based on blackface caricatures. In his pilot film and his first theatrically released cartoon, he even spoke with a stereotypical black accent. Later cartoons gave him a falsetto voice. Despite his appearance, however, Bosko was generally portrayed personality-wise (though like many cartoon characters of the time, he had little to no personality) without any of the common black stereotypes of the time. He was depicted as an everyman, a kind-hearted fellow, and above all good-natured. In later years, Ising denied that Bosko was meant to be a black stereotype, but this is rather hard to believe due the fact that he was registered with the U.S. Copyright Office as a “Negro boy.”

Bosko’s life at Warner Bros., however, would not last. In 1933, Harman and Ising got into a budget dispute with Schlesinger. They wanted more money to improve their cartoon’s quality and make them in color. Schlesinger said no, and the two men left, taking Bosko with him.

They eventually found a new home at MGM. They created the Happy Harmonies series, which debuted in 1934. Bosko appeared in two cartoons with his original design. Then he was redesigned as a realistic black boy, which seems to provide more proof Bosko being conceived as a black caricature. However, he was unable to reproduce his success. Eventually, in 1938, Harman and Ising were let go by MGM because they regularly went over budget with their cartoons. MGM created their own in-house cartoon studio.

Bosko remained largely forgotten in decades. His cartoons got their best exposure in a long time, when in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Nickelodeon aired them as part of their showing of the Looney Tunes. However, they were soon removed.

Bosko and his girlfriend Honey appeared on an episode of Tiny Toon Adventures called “Fields of Honey,” where Babs Bunny attempts to find a female cartoon character to have a role model, and she helps Honey, and as is eventually revealed, Bosko, to find a new audience. This episode redesigns Bosko and Honey as dog-like characters, who resemble the main characters of the Animaniacs.

Bosko has lived on, despite his obscurity. Many of cartoons have fallen into the public domain, and they have appeared on low-budget home media, YouTube, and even official releases by Warner Bros.

While Bosko may seem dated and insensitive by today’s standards, it is important to not that without him, we would not have the famous Looney Tunes cartoons that we do today.